‘In these days of architectural renaissance…all the world over men are beginning to speak their minds in what is almost a new language in wood and stone, so that the force of new ideas and independent thinking binds fair to outrival the great, Gothic upheaval of the Middle Ages.’

Walter Burley Griffin in his 1913 address to the New South Wales Institute of Architects defined architecture in transcendentalist terms as ‘an art’ that must appeal directly to the soul. Griffin believed that architecture is ‘an abstract appeal to fundamental human capacity to judge of time and space, of rhyme and proportions, as in music’.

USA

Walter Griffin had graduated from the University of Illinois at Urbana in the United States in 1895. The architectural curriculum of the university had a reputation of being very progressive and Griffin studied horticulture, forestry and landscape gardening as elective subjects supporting his architectural studies.

Walter Griffin and Marion Mahony were employed in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Oak Park studio (Walter Griffin between 1901 and 1906 and Marion Mahony between 1895 and 1905) during what is often regarded as Wright’s most creative period. This experience for both Marion Mahony and Walter Griffin was most formative in the creation of their personal architectural styles. Frank Lloyd Wright’s unique architectural style grew out of the Prairie style and the Arts and Crafts philosophy, but gave to it a new aesthetic dimension that borrowed variously from Louis Sullivan’s style, Japanese design principles and contemporary European and British design directions.

By 1910 Griffin had created his own architectural style dominated by geometry, textured stone walls and rough-surfaced wooded trellises. The use of geometry and pure forms drove Griffin’s architectural expression. His architecture is the fusion of the brief, form and context of a site’s attributes, so that the building communicates its inner meaning.

He was passionate about structural form and the use of contemporary technologies such as reinforced concrete as a construction material offering greater freedom of architectural expression. Reinforced concrete technology allowed the building of monumental architecture with large spans and the first high-rise buildings in the late nineteenth century in Chicago.

Melbourne

The Capitol Theatre building and Newman College, both in Melbourne, were the largest and most impressive architectural projects by Griffin in Australia, built between 1916 and 1924.

The theatre building applied contemporary reinforced concrete technology and was designed as part of a ten-storey office building in Swanston Street. The design is based on the Chicago style architecture of Adler and Sullivan in their Auditorium Building of 1889.

The crystalline interior is breathtaking and has a formal affinity with the high movement of German expressionism. The exterior architecture of order and formality is contrasted with the fairytale interiors of the foyers and the theatre interior. Marion Mahony was the architect responsible for designing the interiors of the Capitol Theatre.

Newman College in Melbourne was commissioned to be designed in the traditional Gothic style. Griffin’s design has a spiritual connection to Gothic but the building is free from revivalism. The project is infused with fairytale; it is almost utopian and has atmosphere rich with classical Gothic influences and the masterful use of materials and natural light effects on the interiors.

Griffin said at the time: ‘In these days of architectural renaissance … all the world over men are beginning to speak their minds in what is almost a new language in wood and stone, so that the force of new ideas and independent thinking binds fair to outrival the great, Gothic upheaval of the Middle Ages.’

Both Walter Griffin and Marion Mahony argued for the creation of better environments by carefully planning buildings within their settings and respecting the landscape character of a site.

Castlecrag

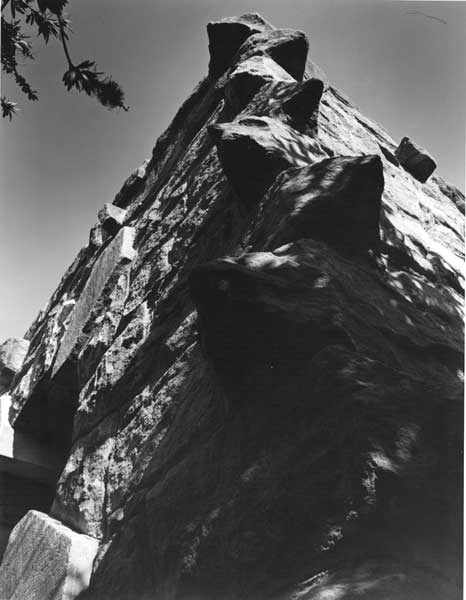

Griffin designed and built 15 houses in Castlecrag, a suburb on Sydney’s leafy North Shore. The houses were carefully located and built using local sandstone or the prefabricated concrete building Knitlock system designed by Griffin. They were placed carefully on individual bushland lots to harmonise with the landscape and to minimise their impact on the natural environment. The houses had stepped setbacks from the road to respect the views and privacy of neighbouring houses. The Griffins’ houses broke contemporary planning conventions, had living rooms located at the rear and opening to the landscape and views, and had utility rooms such as kitchens and bathrooms fronting the street.

The Castlecrag houses had flat roofs and little ornamentation. The richness of the architecture came from the use of local stone as the building material and the subtle placement of the houses in the native landscape context.

India

Walter Griffin left Australia for India in 1935 after receiving a commission to design Lucknow University library. Between 1936 and 1937 Griffin designed approximately one hundred projects. These included individual buildings for the United Provinces Industrial & Agricultural Exhibition. Those built include the Pioneer Press building and pavilions for the United Provinces Exhibition, both in Lucknow.

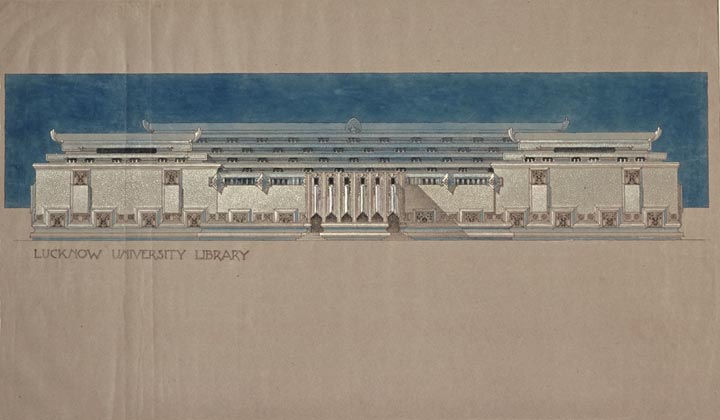

Following his philosophy that architecture must strike a balance between universal modernity and the particular local context, Griffin created a modern Indian architecture whose forms were consistent with his life’s work yet characteristic of their cultural settings. Griffin’s Lucknow University library looks and feels Indian but it was at the time a very contemporary modernistic building. The Indian architecture shares several common characteristics with Griffin’s work: simple, geometric forms with applied exuberant ornament.

Many of the Indian buildings have centralised plans which are rare in earlier Griffin work but common in traditional Indian architecture. The pointed arch with pointed flat haunches rising from curved springers — the so-called Mughal arch — is absent from western architecture but is an ubiquitous motif of the north Indian architecture that Griffin used in his Indian projects. He had experimented with new construction techniques and responded to new sources of visual inspiration.

Griffin was able to create on three continents an exuberant, expressive and innovative architecture reflecting both the ‘stamp of the place’ and the ‘spirit of the times’.

Elevation of Lucknow University Library, second design, Lucknow, 1936. Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University

Detail from Student Union, Lucknow University, Lucknow, India perspective 1936. Marion Mahony Griffin, delineator. Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University

Author

Margaret Petrykowski is the Director of Urban Design in the NSW Government Architect’s Office. She is an architect, urban designer and educator with over 20 years experience of involvement in State-significant projects, such as the civic upgrade of George Street in Sydney and many master plans for suburban centres. Margaret is an alternate member on the City of Sydney Central Sydney Planning Committee.

Further reading

Birrell, James. Walter Burley Griffin Brisbane, University of Queensland Press, 1964

Johnson, Donald Leslie. The architecture of Walter Burley Griffin Melbourne, Macmillan, 1977

Walker, Meredith, Kabos, Adrienne and James Weirick, James. Building for nature: Walter Burley Griffin and Castlecrag. Sydney, Walter Burley Griffin Society Incorporated, 1994

Harrison, Peter. Walter Burley Griffin landscape architect. Canberra, National Library of Australia, 1995

Watson. Anne (editor). Beyond architecture: Marion Mahony and Walter Burley Griffin in America, Australia and India. Sydney, Powerhouse Publishing, 1998