A Capitol idea

Rising above the strange emptiness of central Canberra, the steel structure that crowns Giurgola’s Parliament House traces the pyramidal outline of a ‘significant other’, the Capitol, which Walter Burley Griffin intended for the site. The new flag structure has been considered problematic, unnecessary and even by Griffin’s most sympathetic critic, uneasy — but it is necessary in that a suggestion of Griffin’s most memorable, most enigmatic architectural idea has been given physical form. It is the first time that an architectural element from Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin’s original competition scheme has approached actuality. Even the bare outline of the idea, appropriated to legitimate another departure from Griffin’s intentions and awkwardly executed, nevertheless has sufficient potency to indict the spiritless modernism of contemporary Canberra and the official culture that has produced it.

Philosophical foundations

This effect, however, is incidental to a critical understanding of the Griffins’ achievement. Marion Mahony’s drawings for the Federal Capital Design Competition contain proposals more vibrant and exciting than anything that has been built in Canberra. The principal significance of the Griffins’ vision for the Australian Federal Capital is grounded in the lived experience of their practice and the peculiarly American world-view that they shared.

The experience of Marion Mahony and Walter Burley Griffin as architectural students and practitioners in the early 1900s coincided with a significant realignment of political and economic forces in the United States. The domestic architecture with which the Griffins were principally involved held out the possibility of refuge from the social conflict and contradictions of the time for a certain element of bourgeois society. The underlying concept was that the home could become a total work of art and craft in spite of an industrial system that was alienating increasing areas of human activity from creative, individual involvement. This Arts and Crafts movement was, however, torn between standardised sentimental associations and a radical challenge, which began to embrace abstraction, the machine and the process of production.

The young progressives in Chicago — Frank Lloyd Wright, the Griffins and others — like secular architects in other parts of the world, were poised on the edge of negating, not complementing, the bourgeois social order. The situation that made Chicago unique was the intersection at this point of mass corporate culture, implied by that other Chicago genre, the skyscraper. The vast business organisations that occupied the standardised space of the tall office building valued managerial conformity above individuality. In this environment, domestic architecture in Chicago began to reject progressive tendencies and subside into standardised sentimentality. These were the critical forces at work in American architectural life when the Griffins resolved to enter the international competition for the Australian Federal Capital in 1911 and project their ideas into a new realm.

The drawings for the Griffins’ competition entry were prepared in the loft of Steinway Hall, the shared drafting space of a self-aware group of young progressive architects. The studio looked out over low commercial buildings to the tower of the Auditorium Building, once the tallest structure in Chicago that formerly contained the drawing office of Louis Sullivan on its top floor. It was to be Griffin’s mission to take up Sullivan’s ideas and attempt to project them beyond abstractions into the actuality of political institutions. This was the opportunity offered by Australia and as the scheme took shape in the loft, the atmosphere must have been subliminally charged with Sullivan’s injunction:

‘Current ideas concerning democracy are so vague and so shapeless, that the man who shall clarify and define, who shall interpret, create and proclaim to the image of Democracy’s fair self, will be the destined man of honour: the man of all time.’

Griffin’s Canberra

Griffin set out to clarify and define, interpret and proclaim the essence of democratic experience. His plan for the Australian Federal Capital would be charged with self-evident truth and its public landscape would have meaning for every citizen. By simple moving about the city, engaging in everyday life, the powers and responsibilities of government institutions, together with the rights and responsibilities of each individual, would become manifest. Griffin set out to give physical form and tangible reality to what he believed was an ideal democracy. As he subsequently explained:

‘I … entered this Australian event to be my first and last competition, solely because I have for many years greatly admired the bold radical steps in politics and economics which your country [Australia] has dared to take, and which must for a long time, set ideals for Europe and America ahead of their possibility of accomplishment.’

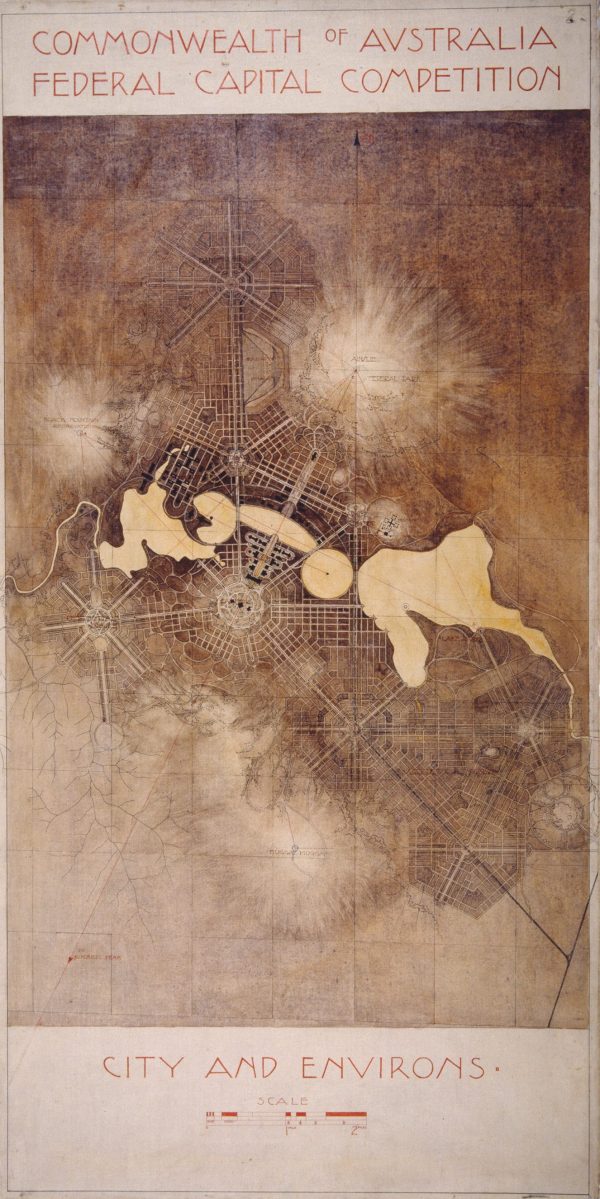

Griffin had remarkable abilities as a landscape architect. From the material available to him in Chicago he was able to grasp the significance of Canberra’s regional setting, to completely visualise the site; to seize the strategic points; develop great vistas; adjust to subtle changes in relief; work with water, land and sky; and introduce as a common theme, the life-force of nature. The essential organising principles of Griffin’s plan were, however, his socio-political idealism and manifest symbolic intent.

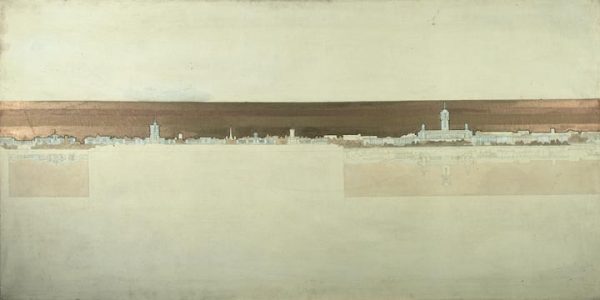

These were combined in his extraordinary scheme for the central part of the city. Across the broad valley of the Molonglo he inscribed a great triangle aligned on the mountains that rose above the site. The triangle was defined by tree-lined avenues and spanned the central basin of an impounded lake. For the base of the triangle, Griffin envisaged a continuous zone of activity – a commercial terrace, backed by the premier shopping street and a residential district of courtyard apartments. The commercial terrace would overlook the central park of the city, which would reach down to the northern shore of the lake. Various public institutions and cultural facilities would be sited within this park.

With its walks and drives along the water’s edge; its cultural institutions; its national sporting venues; its vital links with everyday life of the city’s business district, the Central Park of Griffin’s Canberra was conceived as a people’s park – the principal place of spontaneous congregation in the capital. In Griffin’s scheme, the base of the triangle would be – the people.

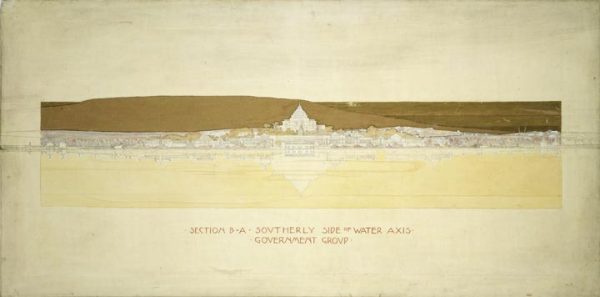

Looking across the lake to the Government Centre, the completion of the triangle would express in compelling physical form, the will of the people. In the Griffin Plan, the Houses of Parliament, though prominent, would not crown the ensemble of government buildings. On the higher Capitol Hill was the climax of the whole scheme. There the convergence of the avenues was resolved in a rotary sweeping around the crest of the hill, marking out the site of three significant buildings. Two of these, although small in scale, gained significance by their function and setting. The first was the official residence of the Governor-General; the second the official residence of the Prime Minister. Both were sited at the apex of the triangle to emphasise the central place and importance of the Executive. However, the view over the Houses of Parliament to the central park and activity centre of the Capital affirmed that the Executive would require the support of Parliamentary authority and ultimately, the support of the majority of the people.

The central triangle of Griffin’s Canberra thus arranged the functions of government in relation to the life of the city to express the very nature and working of constitutional democracy. At one level, this exercise was a timeless, universal statement on the meaning of the democratic experience. But it was fixed in the Australian context by two devices: the alignment of the great triangle on the Australian landscape, the bushland preserves of Mount Ainslie and Black Mountain; and the focusing of the avenues on a building uniquely expressive of Australia. This was the building Griffin designated the Capitol, the third structure planned for Capital Hill. Sited in the most prominent position in the apex of the triangle, Griffin envisaged this building to be a place of popular assembly, a repository of the national archives and an institution commemorating national achievements. Shown in Marion Mahony’s drawings as a stepped pyramid with a vast vaulted interior, the Capitol was conceived as a temple dedicated to the national spirit, an expression of the collective genius of the Australian people.

The entire scheme was conceived in terms of a great theatre:

‘Taken together, the site may be considered as an irregular amphitheatre – with Ainslie at the north-east in the rear, flanked on either side by Black Mountain and Pleasant Hill, all forming the top galleries; with slopes to the water and auditorium; with the waterway and flood basin, the arena; with the southern slopes, the terraced stage and setting of monumental Government structures, sharply defined, rising tier on tier to the culminating hill of the Capitol; and with the Mugga Mugga, Red Hill and the blue distant mountain ranges, sun reflecting, forming the back sense of the theatrical whole.’

What Griffin was offering was a Rousseauist dream, ‘the dream of transparent society, visible and legible in each of its parts, the dream of there no longer existing any zones of darkness.’ But in the great scheme of things, there would be one mystery. In a landscape offering everywhere the possibility of transcendent experience, there would be one place of immanence. The inner space of the Capitol would suggest the possibility of oneness – it would offer above all, a place of psychic repose and resolution.

The Griffins’ position is now clear —the aesthetic they brought to Australia was profoundly anti-modern, but the lives they lived were radical. It was their social and political ideas that prevented them from being accepted into the bourgeois social order. Thus, in Australia they were propelled into the avant-garde, even though their architecture was totally opposed to the main stream of Modernism.

Paradoxically, their contribution to Modernism in Australia was what they were not able to do — Canberra. Since 1920, the year Griffin was forced to sever connection with the project, the city that has been built in the valley of the Molonglo has used Griffin’s axes, elements of his street pattern, a modified version of his lake system and nothing of his symbolism. To this has been added a minimalist steel outline of Griffin’s central architectural concept, the pyramidal Capitol, the only manifestation of a political symbolism poorly understood by successive generations of politicians and planners.

Author

James Weirick is professor of Landscape Architecture at the University of New South Wales, Sydney. He has written and lectured extensively on diverse aspects of the Griffins’ works and lives. His interest in the Griffins, which extends over thirty years, was initiated through his uncle, Colin C Day, who worked as Walter Burley Griffin’s last articled pupil and who lived with the Griffins at Castlecrag in the 1930s. James is the president of the Walter Burley Griffin Society 2004-6.

Further reading

Harrison, Peter, Walter Burley Griffin: landscape architect. Canberra, National Library of Australia, 1995.

Mackenzie, Stuart, Wood-Bradley, Ian et al, The Griffin Legacy: Canberra the Nation’s Capital in the 21st Century. Canberra, National Capital Authority, 2004.

Reid, Paul, Canberra following Griffin: a design history of Australia’s national capital. Canberra, National Archives of Australia, 2002.

Reps, John W, Canberra 1912: Plans and planners of the Australian capital competition. Melbourne, Melbourne University Press, 1997.

Weirick, James, “The Griffins and Modernism”, Melbourne, Transition Autumn, 1988