When Walter Burley Griffin was appointed the Federal Capital Director of Design and Construction to supervise the implementation of his winning town plan for Canberra, Australia’s new capital city, he was permitted to spend 50 per cent of his work time at his private practice. This enabled Griffin to continue a number of projects in America and Canada, as well as accept commissions from Australian clients.

Walter Burley Griffin first settled in Sydney, forming a brief partnership with J Burcham Clamp who had astutely sought out a friendship with the Griffins in Chicago in about 1913. However the partnership was dissolved in 1915 when it became necessary for Griffin to move to Melbourne, as the Federal Capital Office of which he was Director, and the Ministry of Home Affairs (under King O’Malley) were both in Melbourne. The Federal Capital Office was for a time at 84 William Street, Melbourne and so Griffin rented an office nearby in Room 9 on the 7th floor of 395 Collins Street.

Early work including Newman College and Café Australia

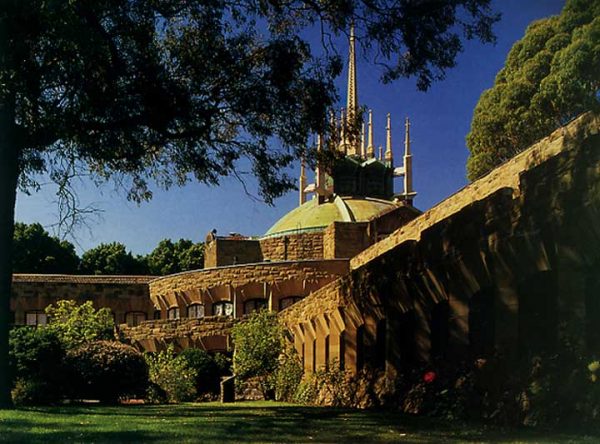

This office was also conveniently located being on the same floor as the office of the architect Andrew Augustus Fritsch who had been engaged by the Building’s Committee for Newman College, together with Griffin, to design the first Roman Catholic residential college, adjacent to the University of Melbourne. Fritsch gave Griffin a free hand in the concept design of Newman College, which is considered to be one of Griffin’s finest buildings. Newman College is included on the National Heritage List. [www.deh.gov.au/heritage/national/sites/newman.html]

Griffin’s first building commission in Melbourne was the rear extension to Collins House at 381 Little Collins Street, which he designed in an informal association with Eggleston and Oakley in June 1914, only one month after he settled in Australia. Griffin declined to accept any fees for his design, and so the client, Mr. Baillieu, gave him a gold cigarette case. The completion of Collins House precipitated the Griffins’ falling out with Captain George Taylor and his wife, Florence, who having campaigned fiercely to bring Griffin to Australia to ‘save Canberra from the bureaucrats’, described Griffin’s modernist Collins House, in their Building magazine as ‘Freak Architecture’ in 1914.

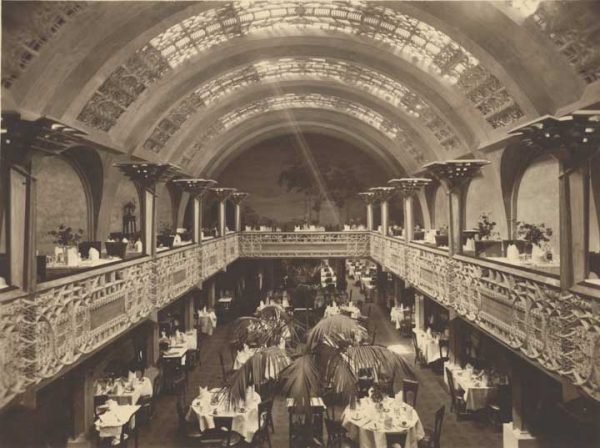

However Griffin’s architectural reputation was soon repaired and enhanced in the eyes of the Melbourne public when the sumptuous Café Australia was opened in Collins Street during World War I (May 1916). Griffin had transformed the old Vienna Café of Antony JJ Lucas, the internal remodelling and combining of the former Glen’s Music Shop next door creating an extraordinary and dramatic restaurant. So pleased was Lucas that he commissioned Griffin to remodel his bayside mansion, Yamala, at Frankston. A year later Lucas engaged Griffin to re-landscape the whole Yamala property including the surviving driveway, pergola and the distinctive Yamala gateposts, which now form the entrance to Yamala Drive.

With Griffin heavily committed at the Federal Capital Office during 1917, his wife, Marion Mahony Griffin, had time to become involved in the women’s branch of the Town Planning Association as well as to accept a private commission for a family residence for Richard Reeves. The working drawings were completed but the builder’s quotation was in excess of the client’s financial limit. Reeves refused to pay any architectural commission to Marion Mahony who suspected that he might later proceed to build the house (even if in a modified form), so she patented her design as ‘a Work of Art’ with the Australian Patents Office. When Reeves built his house in a simplified and altered form of Mahony’s design, she took him to court to recover her fees. However Judge Eagleton ruled that a house design could not be copyrighted and dismissed her claim. This unfortunate incident dissuaded Mahony from ever doing further independent commissions in Australia. From then on she contented herself with assisting her husband’s career.

Having learned of Griffin’s ability to design residential subdivisions, William Towler, a real estate agent specialising in the subdividing and sale of land surrounding large mansions, befriended the Griffins and subsequently engaged Griffin to design a land subdivision in Noojee, Victoria. So beautiful was the setting of the Noojee land that it was not developed but acquired by the Government of Victoria as part of the Latrobe National Park on the banks of the Latrobe River.

Knitlock cottages and other residential commissions

Griffin designed a house for William Towler at Castlecrag, NSW while he was a shareholder in Griffin’s Greater Sydney Development Association (GSDA). Towler had two adjoining Knitlock shops built at Edithvale, one of which became his suburban real estate office.

In order to promote land sales of his 88-lot Grange Estate on Oliver’s Hill, Frankston, Towler allowed or encouraged Griffin to build two prototype Knitlock cottages (Gumnuts and Marnham) on the Estate (1919). This enabled Griffin to test his Knitlock construction technique. While the cottages were owned by Towler, the Griffins were free to use Gumnuts Cottage as a weekend retreat by the bay whenever they wished.

After being appointed for a third three-year term as Federal Capital Director of Design and Construction (FCDDC), Griffin and his wife, Marion Mahony, designed a large two-storey Knitlock house for their private home, but with the entire lower floor set apart as their architectural office (1920). Griffin had purchased what would have been considered by most as an ‘unbuildable’ allotment at the northern end of Kooyong Road, being the remnant corner of the Myrnong Estate behind the old stables, triangular in shape, bordering on a steep railway cutting and falling steeply down from the Kooyong Road frontage. However Griffin, in his usual style, saw the potential of the site. The steep slope made it possible to design an upper level of the house at street level, with a basement level cut into the fall of the land. The house was designed not to face the street, but to face the spectacular views over bushland and the Yarra River flowing due south.

Griffin had to convince the Malvern Council that his patented Knitlock construction was a suitable material for a home in the wealthy suburb of Toorak. To obtain a building permit Griffin had to guarantee that he would personally supervise the construction of the house. Unfortunately the Council’s procrastination delayed construction to the late 1920s when Griffin’s tenure as Federal Capital Director seemed soon to be terminated in favour of a Federal Capital Advisory Committee. The Griffins decided not to proceed with this project and because of their uncertainty whether to live in Melbourne or Sydney, built a replica of Gumnuts Cottage on their vacant lot on the Glenard (Mount Eagle) subdivision adjacent to Roy and Genevieve Lippincott’s house. The Griffins and a chicken farmer built it themselves and named it Pholiota—the mushroom that sprang up overnight. Mahony said (in her memoirs, Magic of America) it was the cheapest and most perfect house ever built. The Griffins then planted and cultivated the garden which was so beautiful that they walked backwards when leaving for the office each morning to feast their hungry eyes on the garden for as long as possible.

The Griffins sold the land in Kooyong Road to William R Paling who in turn commissioned Griffin to design his two-storey house in Knitlock in 1924.

The Paling’s neighbour, who had converted the old Myrnong stables into a comfortable home, was a Toorak property investor who became one of Griffin’s best Melbourne clients, Mrs Mary Williams. In 1922 Williams commissioned Griffin to renovate the interior and front facade of a double-fronted Victorian style house at 74 Clendon Road, Toorak. In 1925 she commissioned Griffin to design a two-storey block of four rental flats at the rear of an existing house, which she named Langi. In 1926 Griffin remodelled and extended the existing house, Langi, into a further four flats at the corner of Toorak and Lansell Roads, Toorak.

In 1927 Williams commissioned Griffin to design The Cloisters, a sprawling two-storey stone-clad complex of residential flats arranged around a medieval-style two-storeyed cloistered garden. Two caretakers’ flats and an underground carpark with grade access from Orrong Road were planned at the lowest part of the site. There was one car space for each flat. This ambitious project was not built but the beautiful coloured floor plans and perspective have survived. In 1928 Williams subdivided the site into several residential allotments but engaged Griffin to design Clendon Lodge (1928) on the triangular corner lot at Orrong and Clendon Roads.

In 1922, Griffin designed a Knitlock house for Stanley Salter. This commission lead to designs of Knitlock houses for Stanley’s brother, Foster Salter in Brighton and his brother-in-law, Alfred Ewins in Ballarat. Only a tracing of the Ewins’ house plan has survived. The Foster Salter Knitlock design was also not built, but the Stanley Salter residence still stands in Glydebourne Avenue, Toorak. It was the second Knitlock house in Toorak and is arguably Griffin’s best Knitlock house design.

Other Knitlock houses were built in Canterbury (1921), Black Rock (1923), Surrey Hills (1923), Heidelberg (1924) and Woodend (1929).

The Wills’ residence at Woodend was designed for Alban H Wills, one of Griffin’s best clients. The firm Wills and Paton of Collins Street had previously engaged Griffin to design two of their Edison shops (1919 and 1927) from which they sold Edison phonographs and records. In 1921 Griffin designed the Wills’ suburban residence at Mentone.

Interior of ‘Pholiota’, at the time it was the Griffins’ home from 1922 to 1925. Reproduced from Segmental Reinforced Concrete Construction, Walter Burley Griffin Society Inc. Collection, courtesy Mary Lightfoot

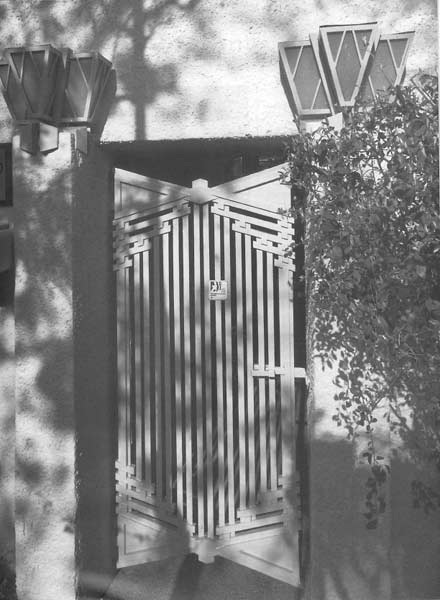

Langi Flats metal grille entry gate and flanking light fittings, 1992. Photographer Mati Maldre, Chicago, Illinois

Commercial and industrial commissions

Griffin and Marion Mahony worked together in Melbourne from 1915 until they returned to Sydney in 1924. However several buildings were designed and built in Melbourne and regional Victoria after 1924, the last being the accommodation bungalows at the YMCA Camp Manyung at Mornington, Victoria (1932). Griffin and his partner, Eric Nicholls, were honorary architects for the Camp Manyung project.

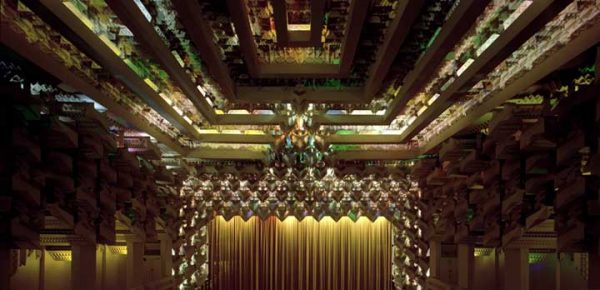

In 1920 Griffin met the Phillips brothers, Harold, Herman and Leon. They had worked at Luna Park in Philadelphia and came to Australia and set up Melbourne’s Luna Park. Their second venture in St Kilda was the Palais de Danse (1920) for which Griffin did the design. Being entertainment entrepreneurs, the Phillips Brothers soon became interested in the moving picture business and commissioned Griffin to design the Palais Picture Theatre (1922). Soon after, the Phillips brothers and Antony Lucas engaged Griffin to design the Capitol Theatre within the ten-storey office building, Capitol House (1924), in the centre of Melbourne’s CBD. The Griffins also designed three other picture theatres, the Orpheum (1922), Ascot (1923) and the Romance (1931), but none of these was built.

Griffin also designed a number of clubs in Victoria. Liberty Hall (unbuilt, 1921), the Henry George League Meeting Room and Library (1921), the Kuomintang Club building for the Chinese Nationalist Party (1921) and the Barwon Heads Golf Clubhouse (unbuilt, 1925).

Griffin did 11 remodelling projects for Sydney Keith including his ladies’ wear store, Holder’s in Bourke Street, and two major city building schemes, theKeith Arcadeproject in Bourke Street and Holder’s Extension building in Swanston Street, both unrealised. In 1926 Griffin remodelled the rear of Sydney Keith’s private home in Caulfield.

In 1921 a modestly successful ladies’ wear manufacturer in Flinders Lane, Nisson Leonard-Kanevsky, asked Griffin to remodel two small shops into one in Flinders Lane. However before the work could commence Leonard-Kanevsky took out an option to buy the vacant site on the opposite corner with money borrowed from Griffin. He immediately engaged Griffin to design a five-storey warehouse for his company. Then Alexander Chambersat 46 Elizabeth Street came on the market. This was a much better site than the top end of Flinders Lane. So Leonard-Kanevsky sold the site, with Griffin’s design for a five-storey warehouse, and bought the chambers. Deeply in debt to Griffin, Nisson again commissioned him to remodel and extend Alexander Chambers. Before a permit could be issued Griffin had been given a new commission, to design a totally new building of seven storeys between the old bluestone rubble walls of the former building. The resulting reinforced concrete and glass curtain walled building became Leonard House (1924), a landmark building in Melbourne until it was demolished in the 1980s. Griffin’s architectural office moved here in 1925 and it is assumed that Griffin did not have to pay any rent.

Just before the stock market crash in October 1929, Nisson Leonard-Kanevsky was persuaded to become the managing director of the Reverberatory Incinerator & Engineering Company (RIECo). Its first design for a municipal garbage incinerator for the City of Essendon was unacceptable, mainly because of the ugly industrial building in which it was housed. Nisson then went to Griffin’s office and requested an aesthetically-designed building to enclose the incinerator. Griffin’s office manager, Eric Nicholls, became RIECo’s supervising architect in Melbourne, while Griffin designed a similar building for the Ku-ring-gai municipal incinerator in New South Wales. The subsequent Griffin and Nicholls partnership survived the great depression years by designing distinctive municipal incinerator buildings for RIECo.

While in Melbourne Griffin and his architectural team entered into several architectural competitions, but were not successful:

- National War Memorial (now the Shrine of Remembrance), Melbourne (1922)

- The Chicago Tribune Tower building, Chicago, USA (1922)

- Two schemes to build over the Jolimont Railway Yards, Melbourne (1925 and 1927)

- Barwon Heads Golf Course Clubhouse, Barwon Heads, Vic (1925)

- Scotch College (now Littlejohn Memorial) Chapel, Hawthorn, Vic (1933)

- Newman College Chapel, Parkville, Vic (1936)

Other built projects in Melbourne

Houses:

- Lippincott Residence, Ivanhoe (1917)

- Reynolds Residence, Canterbury (Knitlock) (1921)

- Hayward Residence, Black Rock (Knitlock) (1923)

- Jefferies Residence, Surrey Hills (Knitlock) (1923)

- V. Griffin Residence, Heidelberg (Knitlock) (1924)

- Cheong Terrace Houses, Carlton (remodelling) (1924)

- Beament Residence, Kew (1924)

- Skipper Residence, Eaglemont (1927)

- Lawrance Row Houses, Armadale (remodelling) (1928)

Incinerators:

- Essendon Municipal Incinerator (1930)

- Brunswick Municipal Incinerator (1930)

Capitol Theatre auditorium with its spectacular crystalline interior and coloured lighting, 1999. Photographer John Gollings, Gollings Photography Pty Ltd. Guided tours of the theatre are organised by RMIT on eight days each year. For more information go to News

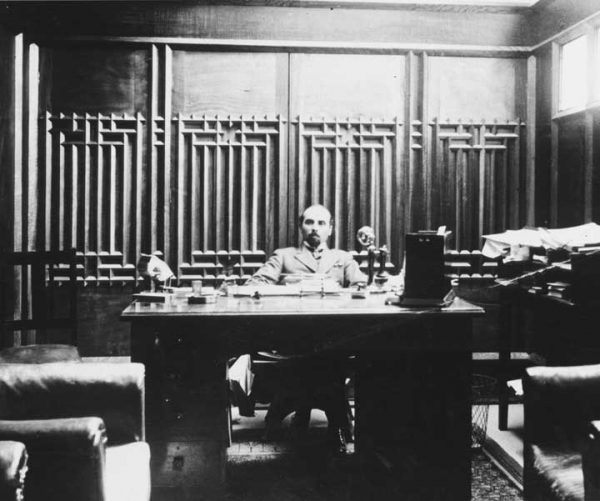

Nisson Leonard-Kanevsky in his office on the fifth floor of Leonard House, 1920s. National Library of Australia

nla.pic-an24475715

Leonard House, 1959. Photographer Bob Meyer

Other unbuilt projects

Houses:

- Brick and rough-cast residence, Ringwood (1919)

- Hume Residence, Braybrook (1920)

- Baracchi Residence, Fairfield (1927)

- Hiddlestone Residence, Eaglemont (1932)

Incinerators:

- Caulfield Municipal Incinerator (1933)

- St. Kilda Municipal Incinerator (c1936)

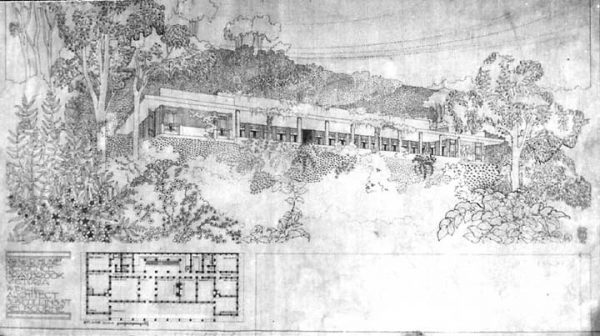

Hume Residence designed for Walter Hume, a director of Hume Pipe Co. (Aust) Ltd. It was the first residential design in which Griffin used concrete pipes as columns. Walter Burley Griffin Society Inc. Collection, courtesy Bob Meyer

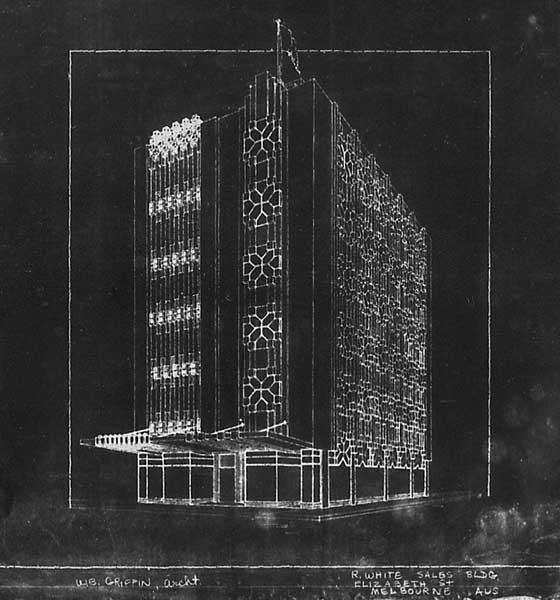

White Sales Building (1922), an unbuilt commercial building at the corner of Elizabeth Street and Flinders Lane beside Leonard House also depicted in this perspective drawing. Walter Burley Griffin Society Inc. Collection, courtesy Bob Meyer

Author

Peter Y Navaretti, an architectural historian, is a heritage adviser within the Australian Public Service. After 25 years of private research on the Griffins and later working as a Research Associate at the University of Melbourne, Peter co-edited with Dr Jeff Turnbull The Griffins in Australia and India: the complete works and projects of Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin. This was the culmination of a lifelong ambition.

Further reading

Harrison, Peter, Walter Burley Griffin: landscape architect. Canberra, National Library of Australia, 1995.

Reps, John W, Canberra 1912: Plans and Planners of the Australian Capital Competition. Melbourne, Melbourne University Press, 1997.

Turnbull, Jeff and Navaretti, Peter Y (eds), The Griffins in Australia and India: the complete works and projects of Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin. Melbourne, Miegunyah Press (Melbourne University Press), 1998.

Watson, Anne (ed), Beyond architecture: Marion Mahony and Walter Burley Griffin in America, Australia and India. Sydney, Powerhouse Publishing, 1998.