Designing for community / the ethos of the Griffins

Marion Mahony Griffin (1871-1961), architect, designer, delineator, and artist, married Walter Burley Griffin (1876-1937), architect, landscape designer and urban planner in 1911. Their architectural practice spanned almost four decades on three continents. The many dimensions to the story of these distinguished American architects stand as a compelling record of their achievements, and demonstrate the continuing relevance of their beliefs and ideals to contemporary thought.

The Griffins’ vision was nurtured in the ferment of liberal ideas at the turn of the 20th century in North America, and developed during the Australian years and, briefly, in India. They were born in Chicago and spent their formative years on the suburban fringes of that great Midwestern city, where they each developed a love of nature and became passionately involved with early conservation groups. They held strong beliefs on democracy, community development and cultural expression, and applied principles and innovations in the direction we know today as sustainability.

The Midwest, with its booming economy and progressive ideals, was the perfect stage for a new architecture to suit new times. Prairie style architecture emphasised simplicity of design and honest use of natural materials to reflect the landscape context. The Millikin Place development, a Prairie School masterpiece in Decatur, Illinois, brought the Griffins together as professional and life partners in 1910, and in 1912 an inspired design for Rock Crest/Rock Glen in Mason City, Iowa, a planned garden suburb based on the integration of landscape and architecture, foreshadowed their sensitive response to the natural topography of the Castlecrag peninsula a decade later. Developed on the site of an abandoned limestone quarry, Rock Crest/Rock Glen is considered the Griffins’ greatest American achievement, ‘a site of latent beauty, neglected but capable of regeneration in a most spectacular way’ (Professsor James Weirick’s chapter of Rock Crest/Rock Glen Mason City Iowa editor Paul Kruty p148).

In 1912 the Griffins won the international competition for the design of Australia’s new capital, Canberra, and arrived in Sydney in 1913. From 1914—1920 they worked on the implementation of the Canberra plan and on other urban planning projects such as Griffith and Leeton in New South Wales and Eaglemont and Ranelagh at Mt Eliza in Victoria.

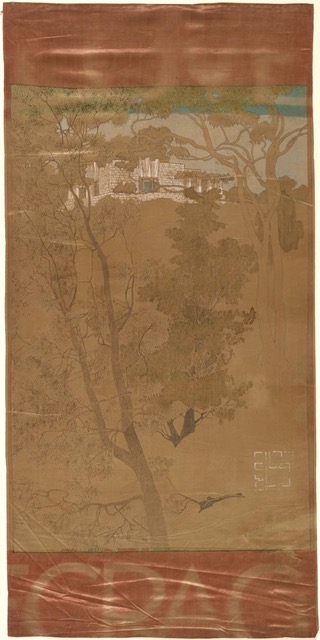

Castlecrag was developed as a model suburb in the 1920s and 1930s. Walter and Marion took up residence in Castlecrag in the autumn of 1925, after many years of travelling between their offices in Melbourne and Sydney, and participated actively in establishing a unique community there. The importance of community interaction, regard for the environment and sustainable living were fundamental to the Griffin ethos. Over the next decade, they lived at various addresses in Castlecrag and designed more than 50 houses, of which fifteen were built.

Griffin’s commitment to ‘organic’ architecture and to the subservience of buildings to the landscape, distinguished his ideas from those of his contemporaries.

The Griffins’ plan at Castlecrag was both to preserve the landscape and natural vegetation of the sandstone terrain, and to create an environment in which a sense of community would thrive. The reserves and walkways and of the Castlecrag Estate, together with the relationship of the houses with each other and the absence of fences, were designed to facilitate a shared landscape and encourage community interaction. Recreational facilities were developed including a tennis court in Cortile Reserve and a nine-hole golf course was developed as the centrepiece of the planned GSDA Castle Cove Estate. Today, Castlecrag continues to demonstrate the Griffins’ deep respect for the natural landscape and their ideal of a community living in harmony with this beautiful setting.

The provision of neighbourhood shops for the community was a priority. Griffin designed the first two shops (demolished in the 1970s for The Quadrangle driveway) in 1922 and two years later another four shops to a design approved by Griffin were constructed: a greengrocer, caterer, mercer and butcher (now called the Griffin Centre) opened for business.

The Griffins were far ahead of their time as regards concern for the environment. Restoring the denuded vegetation on the top of the Castlecrag escarpment was a priority for them and their colleagues such as Edgar and Cappy Deans. The Griffins planted trees that survive today, including a paperbark (Melaleuca quinquenervia) in Lookout Reserve, the tallowwood (Eucalyptus microcorys) at the entrance to the walkway in The Rampart and the lemon-scented gums (Eucalyptus citriodora) in The Parapet.

They and their circle of friends saw their homes as places for work and community rather than the modern view of creating a refuge for the family. A neighbourhood circle met monthly in participants’ houses to discuss topics of local concern, and the Castlecrag Progress Association was formed at a meeting in the downstairs section of the Griffin Centre on 10 November 1925. Edgar Herbert was elected as president and Walter Griffin was on the committee. The Association’s early campaigns were for a government infants’ school, better transport access to the city by construction of an arterial road from East Lindfield to North Sydney (now Eastern Valley Way), the upgrading of Edinburgh Road, undergrounding of electricity wires, sewage services for the peninsula and tree planting along Edinburgh Road.

In the early 1930s Marion had her dream of a local theatre fulfilled when work commenced on the construction of The Scenic Theatre in a natural amphitheatre off The Scarp in The Haven Estate. Walter oversaw the construction, with Bim Hilder undertaking the stonework to create the seating. The first production, in September 1934, was The Sacred Drama of Eleusis by Edouard Schuré, directed by Marion Griffin and Lute Drummond.

After Walter’s death in India in 1937, Marion returned to Castlecrag for a year and then returned to Chicago, writing The Magic of America, a testament, in part, to their life and work together. In a Deed of Trust in 1940, Marion transferred responsibility for the reserves and access ways, including 6.44 km of open space along the harbour foreshores, to Willoughby Municipal Council in trust for the community.

The Griffins and Canberra

The Griffins were attracted to the idea of designing a new capital for a new democracy, but tragically they arrived in Australia at a time when the clouds of war were gathering, and after WW1, many Australians turned inward or looked to Britain and the Empire for reassurance. Conservative thought prevailed in much of middle class Australia. However, Stanley Melbourne Bruce as Prime Minister of Australia 1923-1929 was a constant supporter of the development of Canberra as a national cultural centre and exemplar of Australia’s aspirations, achievements and nationhood.

The Griffin’s design for Canberra, one of the greatest planned cities of the world, was and remains visionary. Griffin developed a unique synthesis of City Beautiful and Garden City elements, against a backdrop of Canberra’s heroic landscapes. He provided a host of grand boulevards, from the central city to the periphery and terminal landscape features. The axial lines, principal avenues, urban densities and mixed land uses were designed to facilitate communication, accessibility, transport and connectedness. Griffin placed great emphasis on public open space along the Lake foreshores and planned extensive parklands around West Basin.

Since 2004 politicians and developers have been promoting a new vision for Canberra, explicitly rejecting the ‘bush capital’, ‘the garden city’ and the Griffin Plan, and opening up the symbolic centre of Canberra to major development. A new era of tower block apartments, higher urban densities, wealthy lifestyles, the service economy, lively precincts and lakeside urban development, prevails. Some of this development has impacted on the Griffin landscape structures that provided the framework core principles for the design of the National Capital.

However, the Griffin vision and plan are nevertheless coming back into prominence. Since the centenary of Canberra in 2013, Walter and Marion have come to be widely held in respect and affection. Residents of Canberra are well aware that the Griffins endowed the national capital with its original, world-prize-winning town plan. We are seeing piecemeal revival of Griffin’s design and principles in the medium density housing along Anzac Parade and Constitution Avenue, the Metro Light Rail and the ACT Government’s commitment to environmental and social sustainability.

Griffin was a lover of nature, landscape architect and planned an organic city in harmony with the natural environment and satisfying human needs. Extensive parks and a variety of street trees were planted under his direction. An early priority was the establishment of urban forests, which contained a high proportion of Australian trees and supported the painting of the hills with differently coloured native trees and shrubs. Protection of the water catchment areas by re-establishing forests to prevent erosion was also a high priority.

Griffin envisaged production horticulture to provide food for the community with market gardens located in the best soils within the city environs. He also envisaged managed forests to sustain construction of the city using the most advanced forestry techniques. He planned the provision of power by a hydro-electric power station at a dam on the Murrumbidgee River. Griffin’s precept of local self-sufficiency was that suitable mixed industries should be nurtured to provide natural resources, materials and jobs, for example his forestry and the cork oak plantation experiments.

Griffin’s Canberra was to have relatively densely populated residential suburbs with three or four storey apartments nestled beneath the trees and an efficient and extensive electric tram system utilising hydro-electric power. Everybody would live within five minutes’ walk of public transport.

Griffin planned a community environment that nurtured children and created safe, healthy and attractive environments for all citizens. He planned the schools to be at the heart of the residential suburbs, built at the centre of the hexagon street plans so that the children’s space was safe at the centre of the community. In 1920 he designed cheap and attractive “artisans’ cottages” for Canberra. He recognised that high-rise development caused congestion as in the American cities, and so planned Canberra “to have a horizontal distribution of the large masses for more and better air, sunlight, verdure and beauty”. (p.30 Walter Burley Griffin landscape architect. Peter Harrison 1995, National Library of Australia).

Further reading

Griffin, Dustin Hadley (ed), The Writings of Walter Burley Griffin. New York, Cambridge University Press 2008

Griffin, Marion Mahony, The Magic of America: http://www.artic.edu/magicofamerica/

Harrison, Peter, Walter Burley Griffin: landscape architect. Canberra, National Library of Australia, 1995

Kruty, Paul and Sprague, Paul E., Marion Mahony and Milliken Place: creating a Prairie School masterpiece with the help of Frank Lloyd Wright, Herman von Holst and Walter Burley Griffin. Walter Burley Griffin Society of America, St Louis, 2007

Mackenzie, Stuart, Wood-Bradley, Ian et al, The Griffin legacy: Canberra the nation’s capital in the 21st Century. Canberra, National Capital Authority, 2004

McCoy, Robert E., Kruty, Paul, Sprague, Paul and Weirick, James, Rock Crest/Rock Glen, Mason City, Iowa: The American Masterwork of Marion M. and Walter B. Griffin, Walter Burley Griffin Society of America, St Louis, 2014

Reid, Paul, Canberra following Griffin: a design history of Australia’s national capital. Canberra, National Archives of Australia, 2002

Reps, John W, Canberra 1912: Plans and planners of the Australian capital competition. Melbourne, Melbourne University Press, 1997

Turnbull, Jeff and Navaretti, Peter Y (eds), The Griffins in Australia and India: the complete works and projects of Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin. Melbourne, Miegunyah Press (Melbourne University Press), 1998

Vernon, Christopher, A vision splendid: How the Griffins imagined Australia’s capital. Canberra, National Archives of Australia, 2002

Walker, Meredith, Kabos, Adrienne and Weirick, James, Building for nature: Walter Burley Griffin and Castlecrag. Sydney, Walter Burley Griffin Society, 1994

Watson, Anne (ed), Beyond architecture: Marion Mahony and Walter Burley Griffin in America, Australia and India. Sydney, Powerhouse Publishing, 1998

Watson, Anne (ed), Visionaries in Suburbia – Griffin Houses in the Sydney Landscape. Walter Burley Griffin Society, 2015

Walter Burley Griffin Society, The Griffin Legacy: Castlecrag Heritage, (brochure). Sydney, Walter Burley Griffin Society & NSW Heritage Office, 2004

Willett, Rosemarie, The National Capital in the National Interest. Canberra, 2019