‘I feel comfortable here and find endless source of interest in the environment of an ancient civilisation’ (Walter Burley Griffin to his father 26 December 1935).

Walter Burley Griffin spent the last 15 months of his life in India. In some respects it seemed ironic that a journey that had begun in the environment of Chicago and the progressive movement of the late nineteenth century should end in what was still part of the British Empire. Yet Griffin’s brief period in India provided an opportunity to unite aspects of Eastern architecture with Western modernism in ways that provided a fitting culmination to his life’s work.

It was through personal contacts, including those of his Castlecrag supporter Ula Maddocks, that Griffin was invited in 1935 to tender for a new University Library in the northern Indian city of Lucknow. Completing most of the design while still in Sydney, Griffin sailed for India in October 1935 intending to be away only three months. Once in India, he soon found a new spiritual home. Set on a level plain beside the Gumti River, the landscape of Lucknow reminded him of the Mississippi Valley of Illinois. For Griffin the converted anthroposophist there was also much to admire in the diverse cultures of Hindus and Muslims that made up the population of Lucknow.

While the Lucknow Library proposal faltered under the constraints of the local colonial bureaucracy, Griffin soon found new admirers, supporters and patrons including the Indian aristocracy. His first major completed project was a zenana—the quarters for elite Muslim women—added to the palace of the Raja Jahangirabad. He formed a strong personal bond with the young Raja of Mahmudabad (who shared with Griffin an interest in the preservation of habitat and wildlife) designing for him a library to hold a rare collection of books and manuscripts. With such patronage Griffin was soon involved in numerous projects. These included homes for academics at the University, a new student union building and municipal buildings for the city of Ahmadabad in western India.

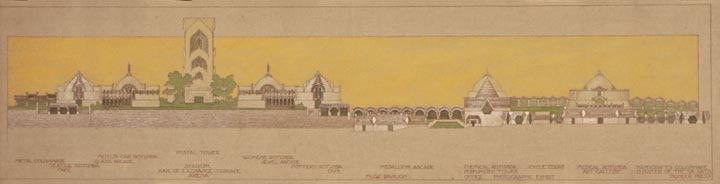

By April 1936 he had been invited to prepare a design for a trade fair to be held in Lucknow. This was a major turning point. Griffin took on the project with enthusiasm. Urged by Walter Griffin to re-establish their architectural partnership, Marion Mahony arrived in May 1936 to assist in completing this work. The United Provinces exhibition was Griffin’s last venture in town planning. He adopted vernacular construction techniques such as bent bamboo and plaster infill. While engaged on the exhibition, he also created a civic memorial to King George V, his only work linked to British imperialism.

In February 1937 Griffin was admitted to hospital suffering from stomach cramps. Operated on for a ruptured gall bladder, he appeared to be in recovery, but peritonitis soon developed. He died on 11 February with Marion Mahony beside him. Buried first in an unmarked grave in Lucknow, a headstone was later built, fittingly in concrete.

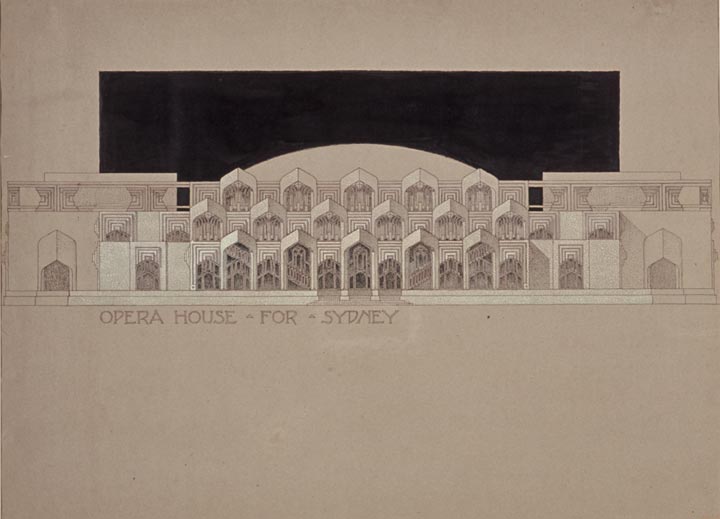

Before he left for India, Marion Mahony had told her sister that Walter’s design for the Lucknow Library ‘looks and feels quite Indian, and yet is the last word in modernism’. Once in India, Walter Griffin admired traditional design: ‘graceful bulbous domes are everywhere…in fact, domes and minarets play the same part in the landscape around here that “eggs and darts” play in Renaissance buildings’. Within a month of his arrival he could even state, ‘In the buildings of all sorts, I recognize most of the “motifs” I have used or even thought of in my lifetime of the practice of architecture’. As Paul Kruty has suggested, the most common feature that was ‘new’ in his Indian work was the ‘pointed arch’—the ‘Mughal arch’—a motif to be found in traditional Northern Indian architecture. Traditional Mughal arches were ornamented in patterns; Griffin’s were without ornament. On the other hand, the expression of the arch as a gable was his own creation. This was just one example of using a traditional motif to create an ‘original’ and ‘modern’ form as he done so often in his earlier buildings in America and Australia. It was this complex relationship between universal modernism and the specificity of locality that remained Griffin’s legacy to India and to the world of landscape architecture.

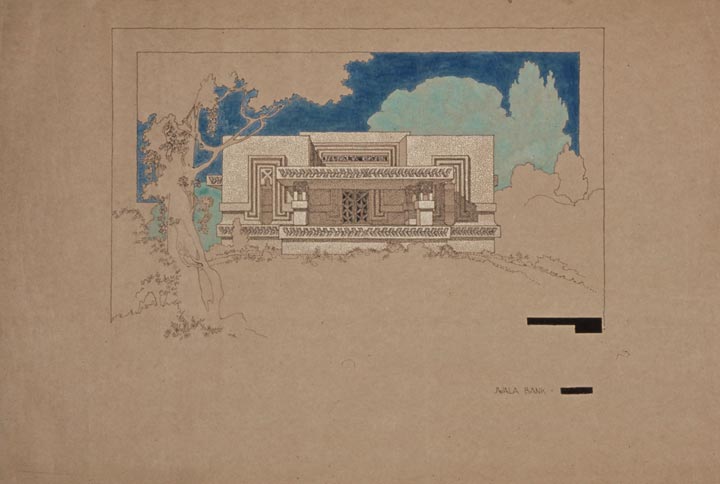

Jwala Bank at Jhansi, India, 1936. Constructed with a flat roof and massive corner piers. Perspective drawing in ink and watercolour on paper by Marion Mahony Griffin. Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York.

‘Opera House for Sydney’. Designed by Walter Burley Griffin originally as extensions to the Ahmedabad Municipal Offices in India. Drawing in ink, watercolour and gouache on linen by Marion Mahony Griffin. Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York. In 1938, a year after Walter Griffin’s death, Marion Mahony Griffin modified the title of her late husband’s design labelling it as opera house. No evidence of a commission or competition has been found.

United Provinces Industrial and Agricultural Exhibition, Lucknow, India. One of two elevations of the trade fair drawn in ink and watercolour on paper by Marion Mahony Griffin. Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York. Walter Burley Griffin designed the 95 acre site plan as well as the numerous temporary pavilions.

Author

Professor Geoffrey Sherington holds a Personal Chair in the History of Education, University of Sydney. He is also a Fellow of the Royal Australian Historical Society and a Fellow of the Australian College of Education. He was previously Dean of the Faculty of Education at the University of Sydney 1997-2003 and Acting Deputy Vice Chancellor 2003-2004. He has been a resident of Castlecrag, Sydney since 1987.

Further reading

Harrison, Peter, Walter Burley Griffin: landscape architect. Canberra, National Library of Australia, 1995.

Johnson Donald Leslie, The architecture of Walter Burley Griffin, Melbourne, Macmillan, 1977, Chapter 8.

Kruty, Paul, ‘Creating a Modern Architecture for India’, in Anne Watson (ed) Beyond architecture: Marion Mahony and Walter Burley Griffin in America, Australia, India. Sydney, Powerhouse Publishing, 1998 pp138–59.

Kruty, Paul and Sprague, Paul E, Two American Architects in India: Walter B. Griffin and Marion M. Griffin 1935–1937. Urbana-Champaign, School of Architecture, University of Illinois, 1997